I had used the montage technique many years before around 1969-70 while working as an apprentice electrician at the Evening Star news paper in Dunedin New Zealand. I fell into the apprenticing through my farther who felt it would be useful to have a trade. Some of my friends at the time were going to art school and I would watch them through the large windows of the great hall that housed the huge press, as they walked up Stuart St with their trendy threads, and bags spewing with art materials. An interesting aspect to this is that by the 1980s none of them continued to make art - although one was a medical illustrator. Of course at that time newspapers had great darkrooms and it was not long before I was sneaking into to experiment during extended lunch breaks etc. Gary Van der Mark who had been trained at the Royal Dutch Academy of Photography was working at the paper and was very encouraging of my work at the time. It was not until about 2004 that Gary told me he was instructed to "keep me out of the darkrooms" and he argued that the work I was doing was highly creative and should be encouraged. So Gary would allow me in to to work when the head of the photographic department was not around. While he went on to run a highly successful commercial photographic studio where he photographed items for junk mail catalogues, in the conversation we had in 2004 he told me he was admiring of my relentless pursuit of my creative work. He said that for years he would see a feature on my work in the paper about another exhibition and then as he walked to work he would see a junk mail catalogue with his work discarded and blowing down the street.

It was ironic that several years later I was involved in photographing the Abbotsford Landslip, and took most of the images published in the newspaper on the event. On the night of August 8, 1979, a major landslide occurred in Abbotsford, resulting in the destruction or relocation of some 70 houses, and requiring the evacuation of over 600 people. No-one was killed. This remains the largest landslip to have occurred in an urban area of New Zealand. Through my good friend Jack Kenyon of the construction department at the Otago Polytechnic I was involved in documenting the unfolding of the event over 2 months. During this time the formation of small cracks in the ground grew larger and larger which caused the gradual destruction of the houses and land as the cracks grew to about 8ft wide and 10 ft deep. Then on the night of August 8th there was a huge movement where the land moved in a dramatic way. While the press were banned from entering the disaster zone, we were allowed to enter the site to document the destruction and I was handed a camera with several rolls of film by a photographer from the news paper - many of these were the images that appeared in the paper and in the special feature on the disaster, unattributed.

Swimming - 1961

I came to surfing through swimming. While his ship was moored in Sydney, my farther had nearly drowned at Bondi Beach, and he vowed that he would teach his kids to swim. As the eldest I was taken to lessons at about the age of 9, but could never get the coordination right. Finally the coach put a life jacket on me and throw me in the deep end, where I promptly swam to the other end of the pool. Straight after that the life jacket was removed and I was thrown in without it, again I promptly swam to the other end. By my 10 birthday I could swim a mile. From here competitive swimming took up a huge part of my life. The mileages crept up until I was covering about 30miles a week, engaged in calisthenics, weights etc. God I would have been a skinny runt if I had not have done any of this.

Surf Life Saving 1965

Swimming introduced life saving and sessions with Garry Marks. From here it was the Brighton Surf Life Saving Club. I remember the club Captain was Wayne Voreth, a fantastic guy who commanded the full respect of anyone who met him. We were returning from a cold surf carnival at Oreti Beach in Invercargill and had stopped off at Gore for something to eat. A verbal skirmish developed from the surf guys and the local hoons that was looking to develop into a full fight. Wayne arrived in the next car and immediately intervened, there was no question from either side and the conflict instantly dissolved. Wayne died in 2008.

When I was 15 I began work as an apprentice electrician at the Evening Star News Paper. We had to work through the Christmas break on maintenance. However this gave a holiday break later in the year. I spent one year in late march camped up in the old Brighton Surf Club. The deal was I could stay there as long as I did a bit of work around the place, like clearing blackberry etc. I collected the blackberries and made jam on the old surf club stove - the wild potatoes that grew in the dunes also got cooked up for a meal. This fascination of growing and collecting food has always remained with me. During the early morning when the surf was good, Wayne Morris and his brother Roy would come down to join me for a surf. They lived in a house in the bay over looking the ocean, and their mother was terribly worried I need a good feed and would invite me up for dinner every few days.

I first became aware of Blackhead in the late 1960s. I had joined the surf life saving club at Brighton, and would often be driven down the long steep dirt road toward the ocean at Blackhead below before the road turned sharply to the right and off to Brighton .

As I moved from surf life saving to board riding, I became much more familiar with Blackhead. While the quarry was present at this point, there were three environmental issues that came to my attention at this time. Blackhead was used as a place to burn the insulation off copper wire.

• Large piles were often heaped up on the ocean side of the headland and burnt off sending black pillars of smoke out to sea.

• Tar distillate was dumped in large pits in the same area, this later seeped out and down the water course that is the small towards the ocean. As far as I can establish this was from cleaning roading equipment operated by Fulton Hogan, and was an unauthorized activity. Anyone who walked down the track beside the creek at this time would remember the black ooze that poured out of the sand and into the water. They might also remember the tricky navigation required to avoid it.

• The raw sewerage that often washed up on the beach |

An image from the poster for the surf movie Javel produced around 1969 produced during my time at the Evening Star Newspaper. |

Because of the unique qualities of Blackhead as a wave,( it is one of the few places near Dunedin that is offshore on a North east wind) I spent more and more time surfing there. I remember great sessions with Jock Benfell, Graham Carse, Kim Westerskov, Tony Ropita, Dave Crooks, Rex VonHuben.As the quarrying began to alter the profile of the headland, I was prompted by John Leslie to walk around and look at the stunning rock formations. Once I did so I realized that these fantastic forms would be under threat. I engaged in a project, where I walked out there and took photographs almost every week for a year. The result was an archive of about 100 - 35mm films - and about 3,500 photographs. During these photographic expeditions, I would often take other artists and others concerned about the demise of blackhead, including Chris Cree Brown, Peter Nicholls, Dereck Ball, Adrian Harrison, Sydney Mann. All were astonished with the fabulous rock formations and were supportive of some form of protection.

From this grew not only the exhibition, Secrets of the Forgotten Tapu, but an awareness that led to the formation of the friends of Blackhead that prompted negotiations with Doc and the Quarry to form a covenant of part of the rock formation. This process involved several meetings with the quarry management and the friends group. The quarries perspective was that because the was no Queens Chain - (originally the rocks were considered too steep to survey0 they owned it all and could mine it to sea level- which was their intention. In fact their ultimate plan was to mine a huge bowl, 50 ft below sea level with and 8- 10 ft wall around the perimeter which would act as a break water. Then on the north east side to cut an entrance that would flood the bowl so it could be used as a boat anchorage. The Maori position was that it was a Tapu place and should be completely left alone. The surfers perspective was that the headland protected the beach from NE winds and should not be altered.

After several meetings a site meeting was called with all parties where an inflatable surf boat transported everyone out to the site for a closer look. From here negotiations continued with DOC and the Quarry management where the covenant was drawn up to protect the selected areas of the formations.

Later in the 1980s, I would drive along the beach from Brighton for a surf.

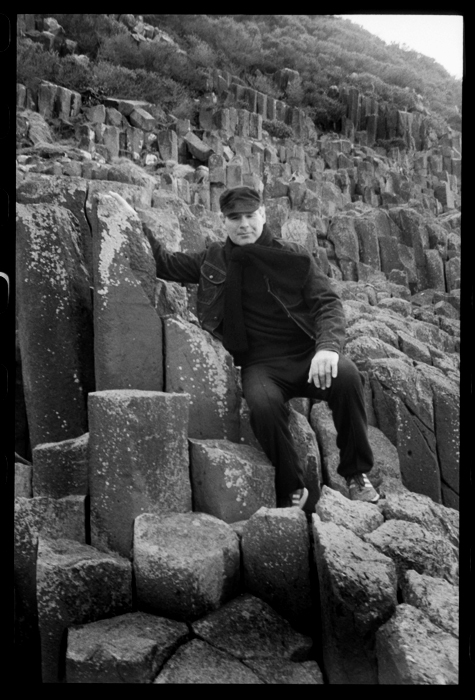

Lloyd Godman centre,

his father Ron, on the left and Lloyd Mayes (shorty) his uncle and name sake with

the headland in the back ground Cir 1987. A scar can be seen down the

headland where the clay over burden had been tipped over the side into

the ocean.

From left, Lloyd Godman's

nephew Richard Stewart, his Niece Rachael Stewart and son Stefan Cir

1989 - the weather worn basalt rocks can be seen on the left spread 100s of meters down the beach.

Lloyd Godman in his old

1953 Land Rover with Sister Wendy in the front with her son Richard

Stewart, his mother Joan back left and wife Elaine right. The Blackhead

can be seen in the far distance

. .

The profile of Blackhead,

Dunedin New Zealand from the southwest side cir. 1980 - note the first cuts into the top of the headland - compare this with the profile in the top image.

I began taking photographs around 1967 – at this point the subject was mainly surfing. I had begun surfing just before then and photography was a means of capturing the exhilarating experience. I surfed just about every week from then until I moved to Australia in 2005. Surfing put me in touch with the ocean’s rhythm. With a few friends I would seek the most isolated places with the most perfect and powerful waves, so consequently we saw some wonderful pristine places. This pursuit for perfect waves often left one sitting on the ocean alone waiting for the next swell contemplating how enchanting it all was. There was a further engagement withy nature.

In 1973 I decided to surf Hawaii with Chris Brock who was a good friend of the legendary George Greenough. George’s footage for the last 13 minutes of the movie Crystal Voyager is a knock out – Pink Floyd composed the music in exchange for the footage for a light show. After the Hawaiian experience, Chris sailed from California to Australia with George, so I was very informed about his work. George has always been a huge influence on me; he is so focused on his work.

While in Hawaii, Chris and I lived at Taylor Camp for 9 months in a tree house constructed of clear plastic and bamboo that wound its way up three stories to the tree’s canopy. The grove of trees was on Elizabeth Taylor’s brothers land close to the beach. The developers were just building the first Condos along the beach front at Hanalei. Hanelei around this time. Coming from suburban Dunedin in the South of New Zealand, a place where walls and roofs were thick and insulated to keep out the cold, and windows were glassed, I was suddenly immersed deep in a tropical nature. It was fantastic!

There were no streets, lights, electricity, etc and for many people it might have been threatening. But I delighted in the sounds of rain on the thin transparent roof, thunder – lightening, the wind through the mesh windows, the sound of the ocean, the wing beat and call of the passing birds, every leaf falling on the roof and the plop of the falling Java Cherries hitting their mark. The moist scent of flowers and leaves passed though the house with every rainfall. At this time I also began a small vegetable and herb garden out the back of the house. The total experience further strengthened my connections and sensitivity with nature. Some of the work from this period was published in Australian Photography magazine Oct 1978.

I continued my practicing my photography and gardening, until, in 1982 the New Zealand Government decided to build the hydro dam at Clyde and flood my favorite river the Clutha. I became highly motivated and was spurred into action on a creative level as I had never been before with a project titled the Last Rivers Song, which consisted of five huge photomurals of the elemental forces of the river gold toned with gold extracted from the river. I carried the surfing experience into the work with the camera often positioned on a long boom over the wild rapids that would be lost to the rising waters of the dam. There was also a series of smaller photo panels that became part of the exhibition. Since this time, ecological issues have remained at the centre of my work.

From 1976 I was exposed to a huge number of books on fine arts. At that time, I had a job making slides for an art school and saw the work of artists like Man Ray, Kurt Schwitters, Joseph Beuys, Richard Long, Christo, Andy Goldsworthy etc. For me it was interesting how their images related to photography. Often photographers see their work as unconnected to the larger world of visual arts.

Over a few decades, my work kept chipping at the fragile edges of traditional photography.

Drawing from Nature, was a combination of photographs drawings. Here a photograph was mounted on a much larger sheet of paper, and I extended the rocks or foliage in the photograph with pen and ink drawings. There were two dialogues – one between the concept of the photograph and drawing, and the other between culture and nature.

Codes of Survival came from an arts expedition to the Subantarctic Islands. These island are wildlife reserves and very pristine places, yet around the coastline all manner of debris is washed up. The resulting prints consisted of a photograph taken on the island in the center surrounded by a boarder of intricate photograms.

Adze to Coda, followed on from this with more combination photograph photogram experiments. The series looked at the relationship of tools and the land and encompassed stone tools to the binary tools we use today. The images for both Adze to Coda and Codes of Survival had the photograph and the photogram printed on a single sheet of photographic paper. They were difficult works to make - often one aspect would be very good while the other let the work down. Exposing for both a good photograph and an interesting photogram often proved elusive.

Evidence from the Religion of Technology), was a series of large colour photograms – the longest work was 22m long, and consisted of three life size figures – a male, a female and a skeleton linked though their outstretched arms by a extensive series of horizontal prints where the dominant colours changed from red, purple to green and back again.

Aporian Emulsions) was an exploration with alternative processes where I painted the emulsion on to create motifs, etc, and then produced photogram images on the sensitized areas. I was researching alchemy and also the history of photography and using emulsions like the Cyanotype and Van Dyke Brown that dated back to the 1840s.

This continual exploring broke the boundaries down, created fractures and fissures in the surface of the traditional emulsion. Light emerged through the gaps as the single unifying factor. During the same period, my interest in plants also continued, I kept developing a large organic vegetable plot, an orchard and an expanding collection of Bromeliad plants.

In 1996 when I began a Master of Fine Art Degree at RMIT in Melbourne, there was a collision that fused both my gardening and photography; my work took a different direction. I came to the realization that my two passions, photography and growing plants both depended on the action of light. Although it had taken about 20 years for me to get there, I later found the Greeks Archimedes and Aristotle made mention of both the camera and photosynthesis. From this intersection came the concept of using plants as living emulsions and growing images into the biotic tissue in a series titled Photo-syn- thesis. I cut lots of alchemic symbols from a special tape and placed them on the leaves of the Bromeliads, the process was similar to a basic photogram where the light is blocked from reaching the sensitive emulsion.

Because I had to expose the plants to the sun for about 4 months to create the photosynthetic images I decided to install the plants in various situations and document the installations. Bromeliads are epiphytes and for me symbolize sustainability, something I feel we need to acknowledge as a species and move towards. So I installed them in locations like coal burning plant rooms, elevators, etc. In works like enLIGHTen, I began suspending Bromeliads in galleries and using infrared activated projectors to project light through them and create shadows on huge tissue paper screens. It was like inhabiting a huge camera, I was playing with light where the only real photograph became a means of documenting the work.

When we use the word photography, the accepted approach is representational photography where a camera and lens are used to photograph the world we perceive as reality. The photograph becomes a surrogate of the real experience. But the marks that make up the subject in any photograph are not reality; they are tonal abstractions that range from dark to light, that reference the actions of light as objects we recognize. The word “photo” relates to the Greek word for light – “graphy” relates to a form of graphics or drawing. What I do is draw with light, its pure “photo-graphy”.

After working on the photosynthetic images on the leaves of Bromeliads, I imagined myself thousands of miles out in space looking at the earth - suddenly the planet became a continually evolving photographic emulsion, an abstract image. It was the result of looking at Nasa’s images - what we see from Google Earth and or astral tripping.

“The largest photosensitive emulsion we know of is the planet earth. As vegetation grows, dies back, changes colour with the seasons, the “photographic image” that is our planet alters. Increasingly human intervention plays a larger role in transforming the image of the globe we inhabit.” 2006

Photosynthesis, as we know it, only comes about through what I call an immaculate exposure. It’s the same as working in the darkroom, or even taking images with a digital camera. Too much exposure and the print is too over exposed and dark – too little and it’s too light and under exposed. Crucial circumstances allow plants to grow on the planet. The earth’s distance from the sun, the atmosphere, heat, light moisture etc. If we alter these factors in a drastic manner, we affect the exposure, the image of the planet becomes either too over or under exposed – we run the risk of an image that’s a reject. However, if circumstances arise where the photo-image of the planet fails, so do humans. Science now confirms we are affecting the levels of electro-magnetic radiation ( light and other radiation) falling on the planet from the sun- we are defacing the beautiful living light sensitive emulsion that is the earth – the image that is our planet.

If we are to solve the ecological dilemma that now confronts us, light, plants, photosynthesis and the giant photosensitive emulsion that is the foliage of our planet will play a huge role.

I like the idea that light feeds us, it sustains us indirectly through the food we eat and also the subjects we seek as photographers – light is a spiritual inspiration. In work like @ the speed of Light, I kept poking into the cracks where the light shone out – kept exploring the margins with plants and self developing photograms. A series of plants were strung up in the gallery and light was projected through them creating enlarged shadows on a large grid of photographic paper. Gradually an image materialized. The images took 2 weeks to self develop through only the action of light in the gallery, and then at the closing I took the prints down and processed them as a performance.

But my exploration into the margins of photo media has never meant abandoning the things that went before, I still enjoy taking traditional photographic images, straight photographs can still have a huge elemental power, a meaningful relevance. All this work has just enlarged my visual vocabulary; no aspect is discarded. Sometimes the simplest things work the best. Recently I was taking a moonlight workshop at Lake Mungo in the Australian desert and by coincidence it was on a full moon. I was really excited with the images I took where I painted the dunes and formations with torch light in combination with the moonlight.

CARBON OBSCURA

In 2007, I was invited to do an ephemeral sculpture by the Nillumbik Shire Council and was given the green house at Montsalvat near Melbourne to work in. The organizers felt I would fill it with plants, but quite the opposite; I was looking for a way to darken the space. I found 1000 sheets of carbon paper for $2 in a recycle shop. It all clicked – greenhouse gasses, carbon and so I covered the walls and ceiling with the carbon paper, and then drew a line of trees (which are the key part of the global carbon trading schemes) by pricking thousands of pinholes in the surface. Carbon Obscura had a fog generator which was activated as the audience stepped into the space, added another reference: we are all responsible for out own gas emissions. But it also brought the rays of light to life in such a seductive kinetic manner that it enchanted the audience and the message became a secondary factor. The installation with the light penetrating the space allowed me to take a fascinating series of photographs that stand alone.

For me the process of making the pinhole work is enlightening, and gives me a greater understanding of light the camera etc. When there is only one hole it works like a pinhole camera. As more holes are created the projections merge and the dominant reference to the pinhole is the diameter of the sun. It’s these bright projections that create the steaming rays through the fog; each ray is a projection of the sun. Later in 2007 I did a similar work, Chambre Noire, at L'Arbre de Vie / Chateau de Blacons, France where the space was larger and the pinhole drawings covered the ceiling as well, which was even more spectacular.

When I began making the first pinholes in the Chateau de Blacons work, I used a digital camera to do some portraits with the pinhole projection of the château onto a large screen and people standing beside it. Then as I made more pinholes there were more and more chateaus until the images blended together. However when the sun was shining, each pinhole projected an image of the sun. If there were trees and leaves over the sun you could see the shadows, when the wind blew they moved in unison. One 7 year old described it as thousands of violin strings made of light. Kids are so perceptive.

Projects like, enLIGHTen, @ the speed of Light, Carbon Obscura, Chambre Noire, have developed as a means of bringing the viewer and the elemental power and beauty of light together, without the mediating presence of cameras, darkrooms, chemistry and photo paper. Inan elemental way, they are a photo-experience, the essence of photography (drawing with light).

|

Sculptor Peter Nicholls at Blackhead - Photo Lloyd Godman

Concert Violinist Sydney Mann playing in the natural amphitheater at Blackhead - Photo - Lloyd Godman.

|