|

Text - Secrets of the Forgotten Tapu - © Lloyd Godman

Secrets of the Forgotten Tapu - Text - © Lloyd Godman

I first encountered Tinirau, (Blackhead) around 1966, as it is now and has always been - it was a place of power. The attraction then was the surf, large, clean, powerful waves that broke with a force beyond the other breaks we rode in the area. Here the power was magnified, somehow the topography of the ocean floor amplified the swell, focused them into thick southern widow makers kissed with long manes of feathery white spray from the offshore wind that often blew down the valley. In fact it was the only break within 50miles where the easterly wind blew off shore. The immense bulk of the headland broke the wind and directed it funnel like down the valley to the in-coming swells in a manner that produced perfect waves.

But beyond the attraction of the surf, rising from the ocean waters was a huge omni-present silhouette - a dense black head-land of basalt that sat on the horizon further than everyone ventured to paddle. As one waited in the deep waters it was impossible not to be seduced by this magnificent force that lifted from the waters like a shrine. It had a presence that I could only imagine with an ancient civilization before the European rational that now dominated the land. Later in the 1980s I was to find - indeed I was right. |

|

Makereatu

Te Wai oTinirau is the beginning of all things known to the ancient Maori. Tinirau is the place of transition from Gods to man. Evolution begins here, in the waters of Tinirau which was throughout Polynesia and for the for the ancient Maori focus here in Otako, at Te Wai oTinirau. In the realm of Tinirau begins the transition of life in the ocean to life on the land. Many human activities begins with Tiniau-games and dancing, utu and the eating of flesh. The importance of the site to Maori people in the region is considerable, Kirsty Elder (1988) writes) in respect of Makereatu.

“Over the past 2000 years the significance of the site has commanded respect in several ways; firstly holding an important place in Maori culture and tradition, being an ancient tipuna (ancestral) site significant in the creation of the area, and as an integral part of early Maori navigation. For generations of Waitaha and Kati Mamoe people, it was a significant stone gathering site, similar to the pounamu (greenstone) fields of Fiordland. To the Maori, it was an area of regeneration and conservation and as such, was a significant part of their resource management, especially regarding kaimoana.”

Stone gathering from Makereatu was treated with particular reverence, and the process of gathering and working it required the observance of strict and complex laws of tapu, in respect to the tremendous spiritual significance of the site. Makereatu (translated to leave a seed) is one of the two names given. It is a name which signifies the joining together of the ancient Waitaha people and the Kati Mamoe people. Hence the name refers to the time when the seed was complete and the two people became one.

The other name is Te Wai oTinirau (the waters of Tinirau), which identifies the site with the original creation. Tinirau is a proper name. It refers back through the Chatham Islands, Rarotonga, Samoa, Rangiriri and the sacred isles of Motutpu.

Blackhead or Tinirau as it was called by the local Maori, is situated a few km south of Dunedin, New Zealand. It is a spectacular basalt outcrop that extend several hundred meters into the ocean and before the quarrying activity was several hundred feet high.

Tinirau was a sacred or tapu site of the “Over the past 2000 years the significance of the site has commanded respect in several ways; firstly holding an important place in Maori culture and tradition, being an ancient tipuna (ancestral) site significant in the creation of the area, and as an integral part of early Maori navigation. For generations of Waitaha and Kati Mamoe people, it was a significant stone gathering site, similar to the pounamu (greenstone) fields of Fiordland. To the Maori, it was an area of regeneration and conservation and as such, was a significant part of their resource management, especially regarding kaimoana.”

Stone gathering from Makereatu was treated with particular reverence, and the process of gathering and working it required the observance of strict and complex laws of tapu, in respect to the tremendous spiritual significance of the site.

Where the ocean meets the black, basalt rocks of Blackhead a sublime threatening of natural violence dissuades most who venture around the shoreline. Waves most often pound high up the rock faces with a force that can also pull one back into the ocean. At certain points, vertical cliffs present a physical impasse to moral beings, higher up the cliffs lichen becomes a slippery a surface in damp conditions. So it is not surprising that when the land was surveyed the authorities believed no one could walk around the headland and consequently no Queens Chain was included on the official maps. This has meant there was no protection of the rock formation on the seaward edge of the headland. ( the Queens Chain is an area of lad above the high tide line that provides access to all citizens)

During the 19 century, pastoral farming cleared much of the native trees from the land on the north east side of the headland leading up to Tunnel Beach and St Clair, but the abruptness of many areas meant that areas of native vegetation survived, particularly in the harshest areas. However farming on these windswept south facing slopes was a marginal business and the dense black stone of the headland attracted other financial interests. From the 1940s a quarry was established on he site to mine the high quality basalt rock. These activities began in a modest way with small machinery and little visible effect on the profile of the headland. |

Looking towards Blackhead from Tunnel Beach Cir. 1880s |

As mentioned, I first became aware of Blackhead in the late 1960s. I had joined the surf life saving club at Brighton, and would often be driven down the long steep dirt road from St Clair that pointed like an infinite arrow directly at the sea, toward the ocean at Blackhead below before the road turned sharply to the right and off to Brighton.

As I moved from surf life saving to board riding, I became much more familiar with Blackhead. I continued to surf the area for many decades.

While the quarry was present at this point, and the rock crushing activity continued, there were three environmental issues that came to my attention at this time. Blackhead was used as a place to burn the insulation off copper wire. Large piles were often heaped up on the ocean side of the headland and burnt off sending black pillars of thick black smoke out to sea. To my disgust, this practice continued for many years and appeared to be sanctioned by the quarry owner of the time. |

Lloyd Godman surfing Blackhead - Photograph Warren Hawk |

Tar distillate was dumped in large pits in the same area as the burning, this thick black substance later seeped out through fissures in the rock, down the clay bank and into the water course that runs down the valley into the ocean. As far as I can establish this was from cleaning roading equipment operated by Fulton Hogan, who later became owner of the quarry, and was an unauthorized activity. For more than 15 years, anyone who walked down the track beside the creek at this time would remember the black ooze that poured out of the sand and into the water. Amid the collapsing clay, the shifting and the planks placed to step on, they might also remember the tricky navigation required to avoid the black gunge.

Further down the beach at Wardronville was situated an inadequate sewerage outlet. At low tide raw sewage poured out onto the white sanded beach from a broken outlet which was covered at high tide. During a south swell, raw sewerage and other flushed artifacts often washed along on the beach towards Blackhead fouling the water. As a means of reducing the problem, the sewerage outlet was later extended further out into the ocean, but in the 1970s -80s the outlet could only be described as a pathetic attempt to deal with a cities waste. In the council's agenda, the outlet was largely out of sight and therefore out of mind. For years the problem was simply too large to deal with.

By the early 1980s the visual effect of quarrying was evident, not only was the commanding profile of the headland being altered, but clay overburden was being dumped over the side with tons finding its way into the ocean. This spurred me to act. John Leslie suggested I take the time to walk as far around the perimeter of the headland as I could manage, he rightly suggested the rock formations would more than impress me.

So, after working on the environmental issues of the Clutha River dam at Clyde in the Last River Song series of 1983 and 84, in 1985 I began working on the Secrets of the Forgotten Tapu. The project brought the demise of the headland to the attention of artists, musicians,surfers, botanists, local Maori and the general public. From this a group called Friends of Blackhead was formed to lead a protest against the wholesale quarrying of the area.

From an article in the Otago Daily Times, November 3 1985 , the then manger of the quarry Trevor Gray said he also appreciated he quality of the basalt rock. " It makes good railway ballast and road metal". At this time his company had been quarrying the site for 40 years and he was "bemused " at the sudden interest in the columns. About the same time, the quarry was sold to a larger company. Blackhead Quarries Ltd is a joint venture company established in 1986 between Palmer & Son Ltd and Fulton Hogan Ltd. Its principle purpose being the quarrying of rock located at Blackhead on the seaward side of Green Island, Dunedin. As a means of protecting some of the rock formation, Friends of Blackhead engaged in discussions with this company.

During initial discussions John Fulton suggested the company owned all of Blackhead could do what it liked and had plans to mine the centre of the site 50m below sea level and then blast an opening into the ocean crating a safe boat harbour.

However Friends of Blackhead raised the issue of overburden and rocks falling into the ocean as an environmental legal problem that they could not solve. The uniqueness of the rock formations was raised, particularly the Roman Baths and the Dock. In a compromise it was proposed that these areas that should protected. Doc agreed to turn a blind eye to tons of material being dumped into the ocean in return for a covenant on a limited area of the head land and a draft document was drawn up.

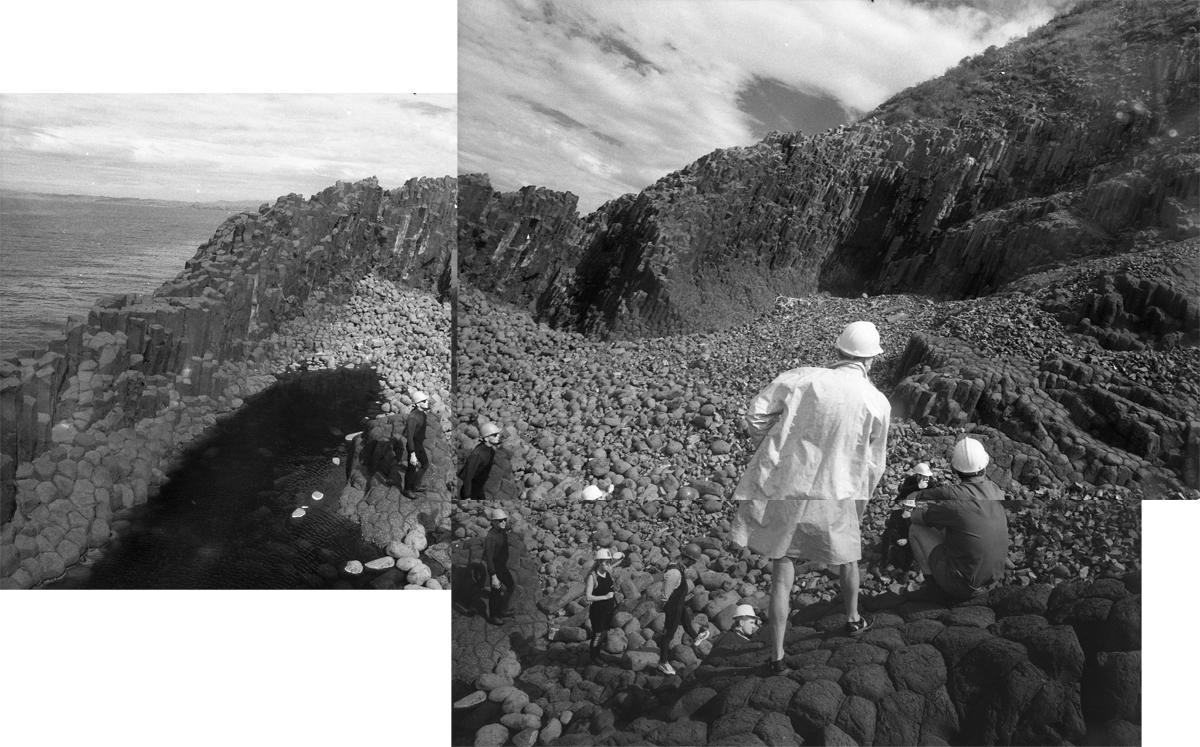

After several discussions an expedition by rubber surf boat was organized to take representatives from the company out to the sensitive spectacular areas at the end of the point. From here a covenant was put in place in 1990, to protect unique rock formations at sea level. However the destruction of large areas of the headland continues creating a strange unfamiliar shape at the end of the point.

I view the quarry management as environmental vandals yet ironically the quarry was the winner of the 1995 Nissan Diesel Environmental Award. |

Fulton Hogan manager John Fulton and Blackhead Quarry manager stand atop on a visit to the Roman Baths area of Blackhead with Friends of Blackhead below to discuss how the area can be saved. 1-2-88 - Photo Lloyd Godman |

|