|

Artist Journal - The Last Rivers Song - The Large Photo-Mural works - © Lloyd Godman

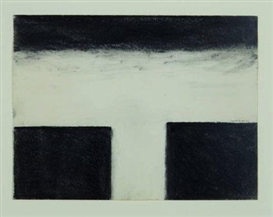

Artist Name: Colin McCahon Title of work: Six days in Nelson and Canterbury

Necessary Protection

Notes on The Last Rivers Song and - DOCUMENTATION FROM TWO PERFORMANCES by LLOYD GODMAN AS A RESPONSE

TO THE COMPLETION

OF THE CLYDE DAM & THE FILLING

OF LAKE DUNSTAN - 1992-3

Prelude I

I

can't recollect, but I'm sure someone once said "change is the only

certainty". The values and attitudes of one society and generation give

way to those of another, and in the twentieth century western societies

this occurs with increasing succession. In the late 1970s through to

the early 1980s in New Zealand was a time when the environment was tested

in a manner that it had not been before, but it was a time when there

was also a response, an environmental awareness.

The early 1980s in New Zealand was a time

when many environmental issues predominated, it was a time when government

rhetoric proposed large scale development of natural resources as a

means of financial recovery and social security. While some strongly

favoured large scale development, others loudly condemned the rhetoric.

It was a time when social division prevailed and the community became

polarized over these issues.

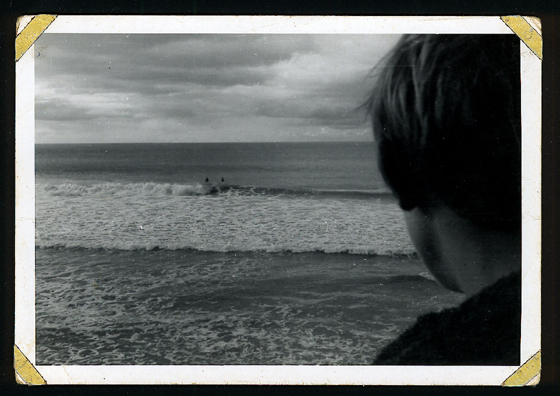

Graham Carse checking the tube at Aramoana. Circa. 1969 |

One of these "think big"

schemes was the proposed aluminum smelter to be built on the grassed

sand flats that converge with the expansive tidal estuary near Aramoana

at the entrance to Otago Harbour in Dunedin. The pro-smelter lobby argued

that the smelter would create jobs, bring growth and prosperity to the

ailing economy of an old stagnating city, while the anti-smelter group

argued that it would be detrimental and irreparably change the environment.

They suggested the effects of the smelter would damage a fragile

environment and associated wildlife, change the life style of

the residents and for these reasons must never proceed.

Aramoana was a place I felt

passionately about, a place that I had meaningful personal connection to, an emotional possession. For me it was a site where a part of "Eden fell"; where

we first cooked baked beans over an open fire, where we watched Carse

set fire to the lupines and the hot tongues of flame licked each strand

of the marram grass as we laughed with a stupid naivety. It was a place

where Dickie showed us the fundamentals of hanging the tail out on the

graveled corners in the trusty Morri 8, a place where we engaged in

our first beer-drinking weekends, although we spilt more than we ever

swallowed, and a place where we discovered something of the nature of

girls. |

Circa. 1968 Aramoana, Dickies crib, Lloyd Godman second from left. |

Aramoana was a place I knew

well, a place where in the late 1960s I learnt to surf in a fun- filled

adolescence, a place where the chill of the south wind coaxed the sun-sparkled

swells with a whispering kiss into the hollow waves we searched for.

A place where the white plumes of spray feathered before shooting skyward

as the swells arched towards the fine white sands between us and the

shore, where a salt rain lashed us as each wave crashed in an ephemeral

crystal vortex. A place where the north east swells had a tempered power

perfect for learning on, unlike the large widow makers that crashed

onto the beach at St Clair and Blackhead. A place where the hot summer

sand barked under scuffing feet that hurried to be some place else,

a place where I first shared the ocean with the small blue penguins.

A place where the royal albatross skimmed miles across the ocean surface

on the flick of a single feather while we strained to paddle the short

distance through the waves to the line u. Aramoana was a special place. |

But long before this it was a place of different

memories, an older nostalgia. A place of family picnics, where the ocean

was cold and unfamiliar and swimming was only for a heated pool. A place

to kick balls, fish, a place of summer salads, cousins, uncles, aunts,

grand-parents, a place to talk and be

a kid in the January sun, a place to take the long climb and eventual

race down the great sand hill blown hard against the even greater cliff

face, as had my mother and her friends a generation before.

.Lloyd's mother with her sisters and friends

on a hockey club picnic climbing the great sand dune at Aramoana. (The

small dots at the base of the central rock by the ocean are people and

give some idea of the scale of the dune.)

Circa. 1946 |

At the hockey picnic, sitting on top of the great sand dune. Circa.

1946 |

Photographs are something

I have always been intrigued with. From as early as I can remember,

I was captivated by their ability to act as depositories of memory,

they allow us to recall with specific detail people, places and events

of our past. In this case, the photographs of my mother and friends,

they create a memory of an event not directly experienced by me. From early in my life, the combined narrative of my mother's memories and

the irregular discovery of the photographs in an album established a

powerful bond between myself and the place that augmented my own experience.

For as long as I could

remember, it was a place I belonged, I to it, and it to me. Before moving back to Dunedin, my life changed and in the intervening

period I moved away for several years, lived in the North Island and

Hawaii, experienced another life I could not have if I had remained. Soon after my return,

the smelter proposal surfaced, and it was an unwelcome intrusion to

my ideals of this place. Like many others, I was convinced that surely

an aluminum smelter would ruin the

essence of Aramoana, with insignificant

reward for the community and the country and I needed little convincing

the proposition must be protested.

It was! From the nation,

as well as the local community, there were out cries for the planning

and project to cease. Environmentalists, scientists, lawyers, recreational

users, families that had lived here for generations, and others that

had recently moved to the area, all protested, and among the voices,

none seemed more poignant than the artists. Prominent figures, like

Ralph Hotere, Andrew Drummond, Chris Cree-Brown, Chris Booth, to name

a few, made significant and powerful work that related to the issue,

they gained publicity and acclaim with exhibitions and appropriate comment

in various art magazines. Initially, because of the involvement of these

artists, I felt I had to be part of this cause too. After all, it was

a place I considered my patch. Around this time I was beginning to regard

my image-making as a more serious activity and part of my life, and

like the other artists, it seemed relevant to link the smelter issue

to my image-making.

Unfortunately, all too quickly

Aramoana seemed to become a fashion, a catch phrase, a band wagon to

climb aboard for the sake of protest, and from my perspective it reached

its peak when a report surfaced, that of a well-meaning North Island

photographer, camera at the ready, was found wandering aimlessly on

the sands of Victory Beach, on the opposite side of the harbour, convinced

he was at the threatened location and making an important series of

documentary images.

While I still felt strongly

about the smelter, and the concern drove a need to comment on the proposal,

I was also concerned about the ineptness of working on a project that

appeared to have adequate comment, a project everyone one and their

dog wanted a piece of. I debated the issues over many months until it

became obvious the planning for this smelter could only proceed under

the rhetoric of the `THINK BIG' schemes promoted by the government.

Rose Kennedy a first love of Lloyd's at Lake Wanaka at the head of the Clutha River - Circa.1969 |

The viability of the smelter proposal was associated with and was indeed

dependent upon another "Think Big " project, the cheap `surplus power'

produced from the proposed Clyde Dam output; an equally dubious project.

Here was another important environmental issue, for the high dam proposal

once completed would destroy a exceptional wild stretch of river and

much of the unique surrounding area. For me it was an equally important

environmental injustice, another saga of `Environmental vandalism'. As with Aramoana, the Clutha river was also

a place of family nostalgia, a place I belonged to.

As with Aramoana, the Clutha

river was also a place of family nostalgia, a place I had emotional possession and one I belonged to, Cromwell, at the meeting of the Clutha and Kawarau rivers was a place

where as a family we had holidayed for many summers, a place where I

had swum with my brothers and sister, friends and relations in the calmer

stretches around Lowburn, where the water quietly curled around the

warm lumps of sand that locals called Sandy King's Islands, as it ran

sea-ward from Lake Wanaka, licking under the lazy hanging branches of

the willow trees. |

At Sandy King's Island, near Lowburn, Lloyd standing on right, his mother

behind Circa.1964 |

It was a place where I had hunted tadpoles

as if they were strange magical creatures that might possess the answers

of life, fished for eels in black waters and flickering fire-light,

slept under the clear inland skies and wondered how large really was

the universe.

It was a place where we

had played a full 9 holes of golf with cricket bats. it as a place where

I had already conducted my own dam experiments, a place here, with my

cousin we had flooded a whole orchard as we experimented with the controls

of an irrigation dam, it was a place where we had also gorged ourselves

on tree-ripe apricots as we picked box full's in recompense. The orchardist had instructed us only to pick the firm fruit that was not yet ripe - the ripe fruit we were allowed to eat. It seemed strange at the time that the best tasting fruit was discarded, and this led to my interest in growing my own fruit that I could let ripen on the tree. First in the garden at Brighton, Dunedin, and then in St Andrews, Victoria. |

It was a place where on

more than one occasion the strong winds and heavy rain had leveled our

tent, a place where in the warm breeze and darkness of a summer's night

I had kissed a first love as the river below eternally washed the rocks

as it ran forever onward to the ocean. And over the summers it was a

place I had always spent hours entranced, watching the water spin and

curl in the blue magic, its depths and white rapids, it was a place

where I had witnessed the evidence of hard rocks torn away by the softness of water,

it was a place where the surge of water pushed a land locked surf, a

place where the river pounded off down the gorge sucking every drop

of water from the black tarns high in the mountains, from the melting

winter snows above.

But from

my very first visit to this environment, I also sensed that here in these

canyons was something of a primeval New Zealand: a quintessence that

only the initiated could perceive, a darker mysterious side to the landscape

that opposed the popular image of yellow poplar trees, blue water, the

delicate cultivation of the orchards, the cheerful escape of a summer vacation. It was a distinct quality that Van Der Velden, McCahon,Baxter,

Hotere had

already perceived, a blinding light against a primeval blackness.

The construction

of the dam seemed to be the crux of the predicament, if there was no

dam there would be no smelter, the two issues were inextricably spliced and

a statement about the dam was

a statement about the smelter. There was much less protest from artists

about the dam, the focus for many had been the smelter, and those artists

that did make comment on the river were perceived as less "vogue"; the

dam issue was not the "bandwagon" the smelter was. So, not only for

its importance as a significant place but because of this unacknowledgement

by the art establishment in 1983 I decided to work with

the Clutha River and not Aramoana.

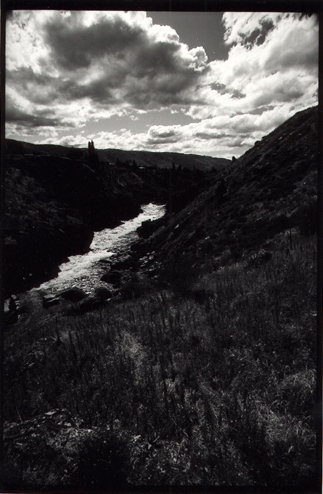

Cairnmuir face and the Clutha River 1984

notice the fruit growers road on the opposite bank of the river. This was eventually flooded when the dam was filled.

On the lower left is a digger undertaking some work for the construction of the dam.

|

From the

outset, I realized that while the smelter protest was much more likely

to succeed, the government was already committed to the dam, if for

no other reason than the fact that political futures were at stake,

and the project was unlikely to be terminated. I was not put off by

the not being able to halt the project, indeed it insinuated a poignancy

in working on a project centred on a place that would be affected, would

be changed forever. Other artists had also worked with the dam issue,

Robin Morrison, a sensitive series of portraits on the residents effected

by the flooding; Marilynn Webb a compelling series of prints called

"Good Bye- Clutha Blue" in 1983 and Bruce Foster a series of cibachrome

prints investigating the pre-construction lines painted on the land,

it seemed none had dealt with the elements that I found compelling,

the essence of the river, the contrasts of rocks and the water,

of solid and fluid, of blackness and whiteness and the spiritual analogy of light against the void.

Eventually,

the protest against the smelter at Aramoana was successful, the proposal

became less an less viable and eventually disintegrated, leaving the

environment intact. However, the dam proposal was one project that despite

logic, cost over-runs, earthquake fault lines under the foundation,

re-roading problems, threatened subsidence on the banks, was pushed

and pushed to completion. |

Initially I researched the area to be affected and from the relevant

information, mapped out the boundaries my project should investigate,

discovered the creeks, streams, the rocks, bluffs, sweeping currents,

swirling eddies that would disappear under the proposed lake. I looked

closer, discovered the names of these features, discovered Byford creek,

Hydes Spur, Sonora Creek, Leaning Rock Creek discovered

Cairnmuir Gully, Gibraltar Rock, Nine Mile Creek, Jackson Creek, Firewood Creek, Deadman's

Point Walker's Creek Banockburn and Molyneux Face, discovered names

to places that I would soon become much more familiar with. But quite

soon, I also discovered there was more at stake than just the flooding

of the "Clutha River", for quite a stretch of the Kawarau branch that

converges at Cromwell and runs down from Queenstown and lake Wakitipu

would be stilled by the dam too, the filling lake was to push up the

reaches two rivers, still the native waters of two rivers, and the loss

of both these areas motivated me to complete this project.

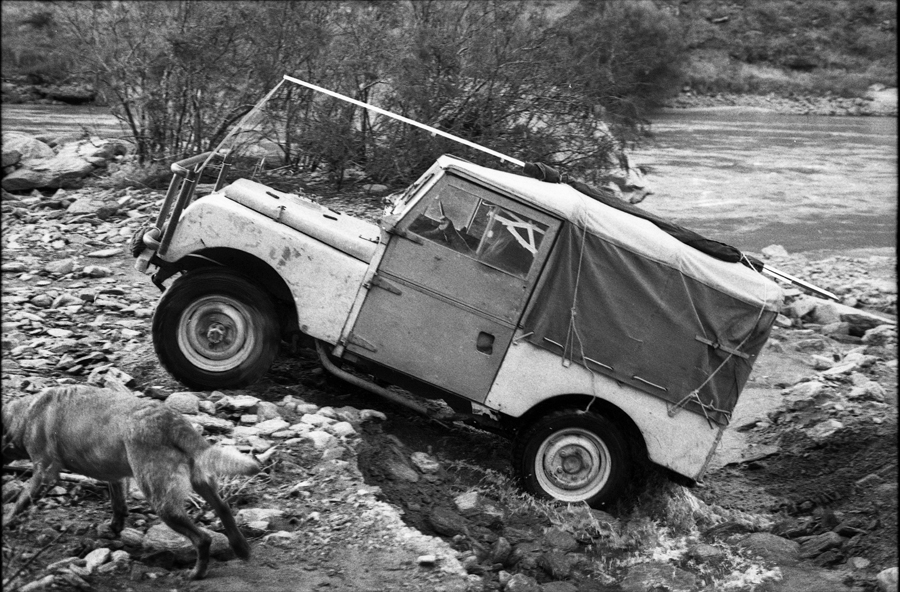

Lloyd's 1953 Land Rover crossing a washed out ford on the fruit growers road - the boom used to place the camera for the water shots is tied to the roof. |

The meeting of the waters below the old Cromwell Bridge - once Lake Dunstan was filled the bridge was submerged |

Detail - The meeting of the waters below the old Cromwell Bridge - once Lake Dunstan was filled the bridge was submerged |

Detail - The meeting of the waters Clutha and Kawarau Rivers below the old Cromwell Bridge - once Lake Dunstan was filled this was destroyed |

Cairnmuir Gully from Clutha Panel IX |

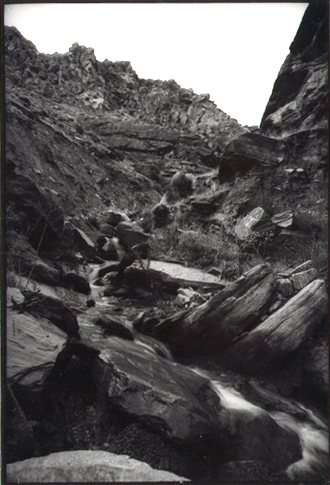

During 1983-4 I made several

expeditions to the area, photographing extensively along the winding

curves of the river that would soon be flooded. I camped with Elaine,

then pregnant with Stefan, our first son, in the immense eerie valleys

and canyons like Cairnmuir Gully that

run up from the river near the fruit grower's road across the river

from the main gorge road so I could photograph the last and first light

on the river, I spent winter days with a river in full flood as the

sleet turned colder to snow and spun shrapnel-like from the sky, I climbed

and crawled over the raw boulder-strewn banks of both sides of the rivers,

I witnessed the sheer chasms cut in the rock over thousands of years,

the huge boulders tossed down the gorge like broken marbles, and I left

only foot marks in the thick silt piled on the bank after a flood, while

all the time taking photographs.

During these expeditions I shot roll after roll of

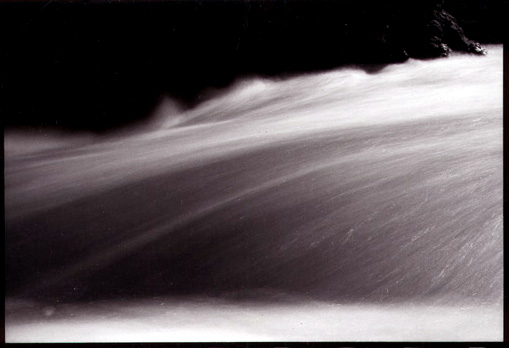

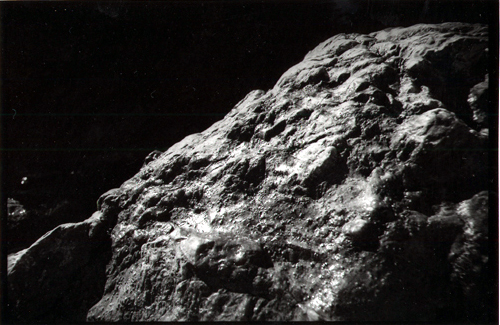

film, always investigating the essential elements of the river |

the reflective qualities of the rushing water - |

the hardness and darkness of the rocks - |

the black and the white. |

For me the true essence

of this river was the relentless force of the water,

the unification of rain drops,

melting snow flakes and ice into a potent force, seeping slowly from

the frozen heights into ever growing trickles, babbling brooks, tumbling

steams, racing creeks, small rivers channeled by the hardness of the

bare rocks into the third fastest flowing river in the world.

The work from this period

was duly completed, exhibited during 1984 as a large series of mural

photographs up to 20' long and a smaller series of photographs,

mounted in sequences that became known as the "Clutha Panels". Later

the work was published in 1989 in a book (Last Rivers Song) with an

introduction by Brian Turner, who was also instrumental in publishing

the work. Despite this and the fact that the dam construction, problematic

as it was, continued in one form or another, I never expected the flooding

to happen, for so many years it appeared so distant.

The Last River's Song -

a poem from 1984 - Poetry

Gone ! the swirling vortexes,

the fly

of spray, the suck and the spit!

Gone! the rapids' roar, the ever-

changing eddies and the crash of foam!

Gone ! the gentle lap of a river

at her

bank and the violence of her flood!

Gone! A River's Song!' |

The Clyde Dam with Lake Dunstan |

Depending whether one was

a procrastinator, engineer, government official, politician, local,

protester or contractor, the completion of the dam and filling of the

lake became both dream and nightmare. Problems seemed to ooze from the

very rock itself, a dyke-like structure with eleven leaks and an insatiable budget.

But finally, after delay

after delay the set time had come, the dam was complete and ready to fill. For some time it

stood awaiting commission like a grotesque great Egyptian pyramid, a

technological wonder waiting for a purpose, waiting for the pharaoh

to die. The was main highway was stabilized, enough drainage tunnels

drilled and hill sides removed or secured enough not to tumble down

into the lake, and the river would change forever, would sing its last

song. I was quite dismayed when a date was set and the flooding

would finally begin. As with the earlier series of photographs, I felt

I had to respond to the irrevocable act, the death of the river's song. I felt

I had to mark the passing in some way, but if I did it would have to

be in a much different manner than the earlier work that celebrated

the rocks and water, a response would demand another quite different

strategy. |

DEATH OF A RIVER - Lake Fill

Series

Ultimately, I had decided on a performance-based

work, a ritualistic ceremony at the very time the water was rising, the old river

dying and the new lake growing. I imagined a ceremony that marked the passing

of the river's flow, a performance that not only used photography to

document the event, but incorporated it as an integral part of the work,

where by the end, a camera would have recorded a vista of the river sequentially

obliterated by the rising water. From 1988, the integration of the photographic act had already become an aspect of my work through the Summer Solstice works. At this time I had also come to realize

much about how the politics of the "Art World" in New Zealand worked and

had decided I preferred to work in a private capacity with the performance. But with assistance these would be well documented.

INITIAL CONCEPT

When I first arrived at

the river \ lake site to carry out the performance work, I had intended

to work from the premise of the lake filling with water as the authorities

had stated in a newspaper item a few days before and I had confirmed

during my telephone conversation with Electricorp officials to gain

clearance to work on the lake shore. During this period, they had calculated

the lake level was to be rising at 2m a day, which I had estimated would

allow me to lie prone at the water's edge for about 3hrs, mentally absorbing

my body into the soil, becoming part of the earth, but at the same time gradually

becoming drowned as the land around me submerged with the rising water

level.

As it turned out, on the

day I had traveled up to the site to complete the performance, coincidentally,

Electricorp were testing the diversion gates and the lake levels were

fluctuating wildly both up and down. This created a problem with the

concept of my original hypothesis and I had to quickly adapt and reconceptualize

the work to suit the situation and the environment I now found myself

in. However, I felt by the end of the work, this modified concept brought

stronger aspects to the work, brought a degree of sophistication, brought

more of a challenge both to me and the viewer than the earlier idea.

It related to the sense of place and the event with a range of iconic,

symbolic and indexical references.

While the rhetoric of image-making

might assume an intention, and audience, these presumptions can be undermined

or at least minimized. The intentions of this work are somewhat explained

in the text, but the audience of the performance would be exclusive

and include only a few friends who were willing to document the event

with both video and still cameras.

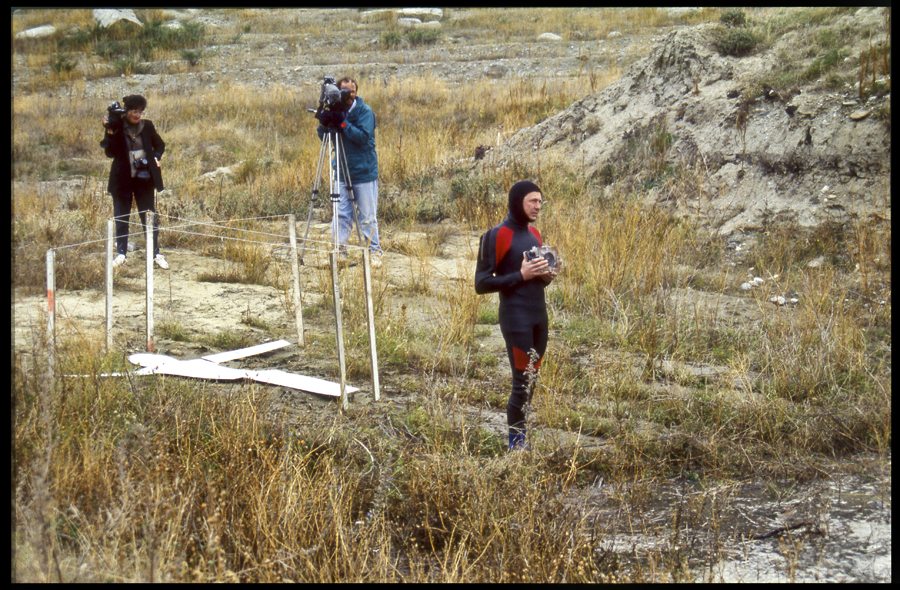

The work involved a private

performance acted out in a ritualistic manner with two friends, Ludmilla Sakowski and Eng Teong Low and

a television crew to document the work.

The physical movements were slow, methodical and mostly intentional.

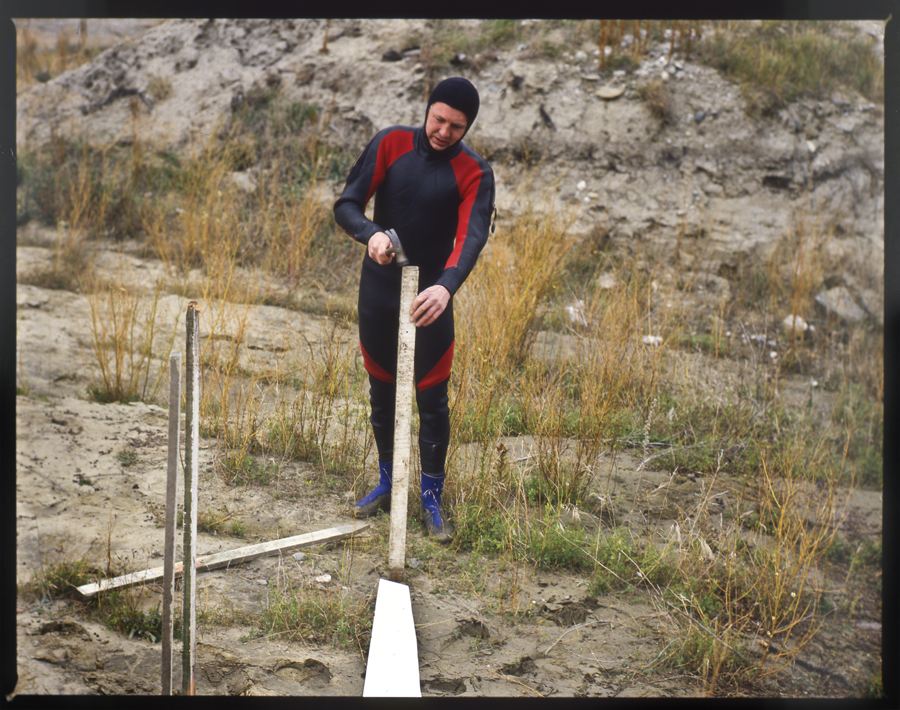

Initially, a variety of construction tools and materials needed for

the work were laid out neatly on the coldness of the bare earth near

the selected site. Some distance away, and out of sight from the viewers

I changed into the insulated security of the black dry suit which had

now became the `ritualistic costume'.

At this point the work proper

started, and in this black costume I became a strange silhouette, seemingly

out of context with the yellow dry autumn earth of Central Otago, I

walked slowly, robot like, toward the chosen site.

Emerging from the infinite space of the land I directed my presence

to the selected area for the work, becoming visually larger to those

few watching with my every step. Once the imagined performance precinct was reached

I selected from the tools, equipment and materials arranged on the ground,

several pieces of pre-cut white cardboard. |

|

|

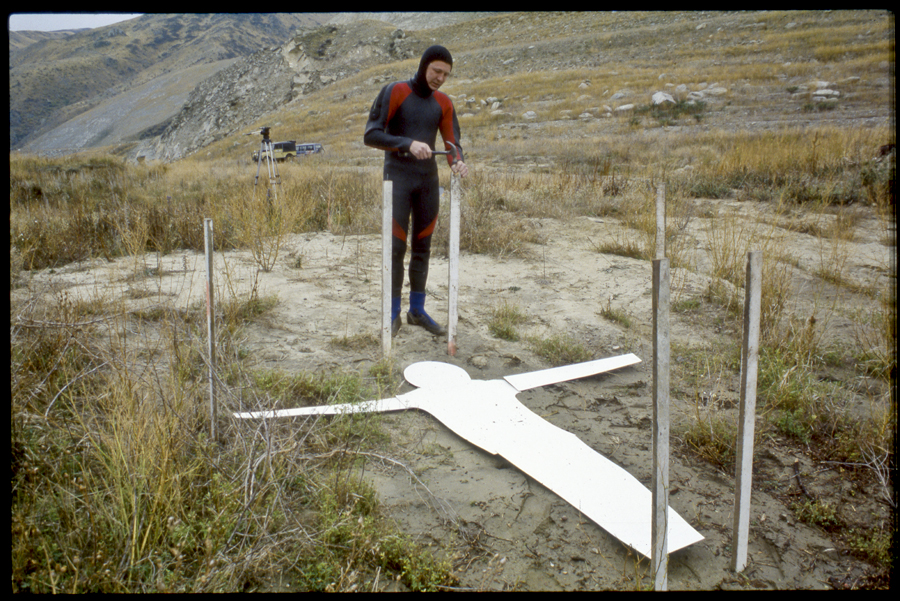

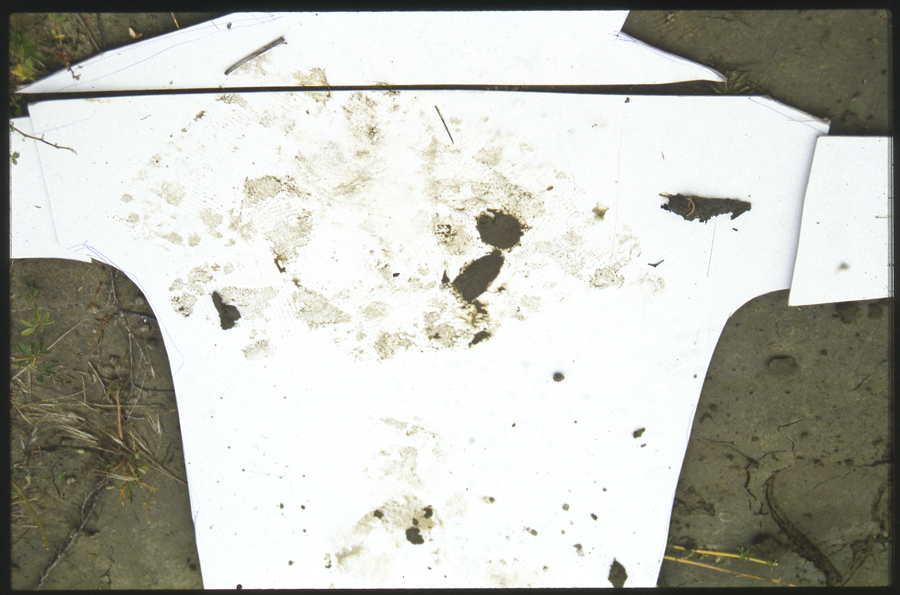

In deliberate motions these were

taken to a pre-selected area of bare of ground near the rising water

level and the parts were laid out to construct the positive white shape

of a human figure with both arms outstretched to form a cruciform. |

|

|

|

This

formed a white shadow of the raw earth itself. Next, a discarded surveying

stake was picked from the assortment of materials previously laid out,

and hammer driven with the same ritualistic mannerisms. With an almost

robot-like style the stake was driven into the ground at the feet of

the bright white cut-out figure on the earth. |

Five more times, a stake

was selected from the pile and was calculatedly driven into the earth,

until there were in all six stakes forming the unmistakable shape of

a crucifix surrounding the white card figure. Two were at both the head

and the feet, while another two denoted the ends of the traverse that

were the extended arms. |

|

|

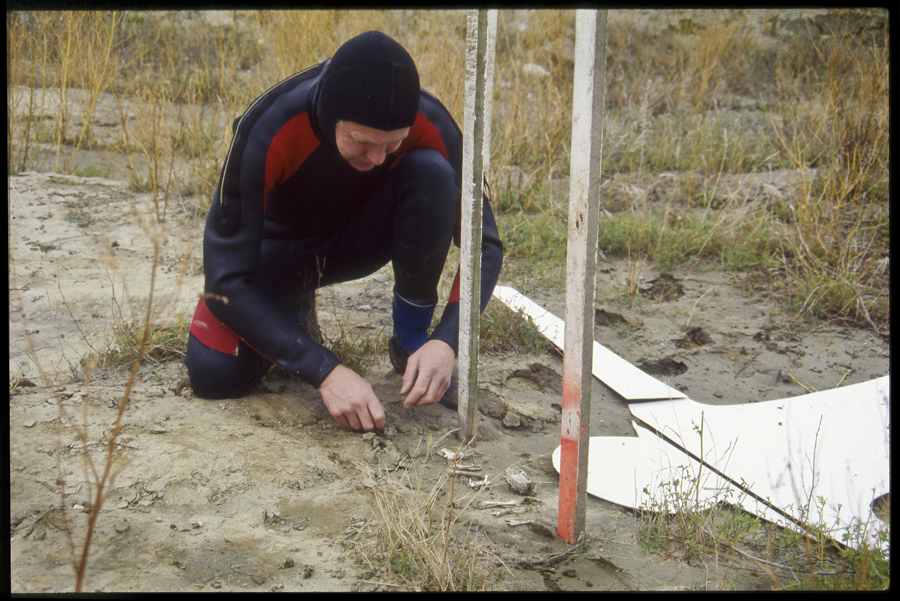

Again, systematically, a

small nail was driven into the top of each erect post, and between the

stakes I strung the taut lines of a fine white charting thread that

clearly defined in another space the plan of the wooden skewers that

confined the body shape on the naked earth below. |

| (Firstly the earth

is ominously dissected by the imaginary lines of the surveyor, the thin

line on the plan; severed and gashed by the ingenuous mark in the intangibility

of imaginary space.) Next I elected

to use a thick felt pen from the array of materials and tools at my

disposal and on the upright posts I rewrote the sun-faded word

"FILL" that already existed from a previous life, a previous surveying. |

|

|

By fate, there in the broken

autumn grasses, in proximity to the performance site, lay the bleached

bones of a dead animal, a rabbit. A poor creature removed against its

own will to a foreign land in a thoughtless act, and now, because of

a saturated population and the effects

of the associated erosion, its kind are despised and exterminated as

a pest to this unfamiliar environment. The rabbit was a national symbol

of an earlier environmental miscalculation! |

| As a homage and with

utmost providence, these few humble dry bones were gathered from their

secret position and arranged with prominence, on the hard river silt

at a place above the head of the alien white figure; with the rotting

skull as a centre piece of the arrangement. |

|

|

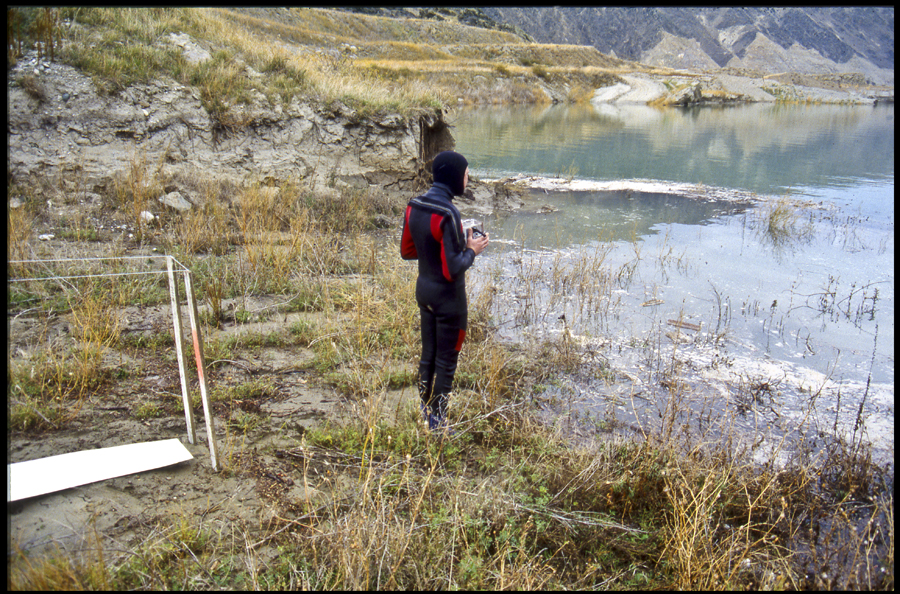

Then, with this simple but

metaphorical installation complete, I gradually moved towards the water's

edge, with a camera surrounded by the insulation protection of an underwater

perspex housing, firmly gripped by both hands against my chest. |

|

|

|

|

|

This

instrument was used as it should be, in the ritual of image-making,

to take photographs from the work site, across the ever-rising lake.

These would be records of a sublime or ridiculous and unique event.

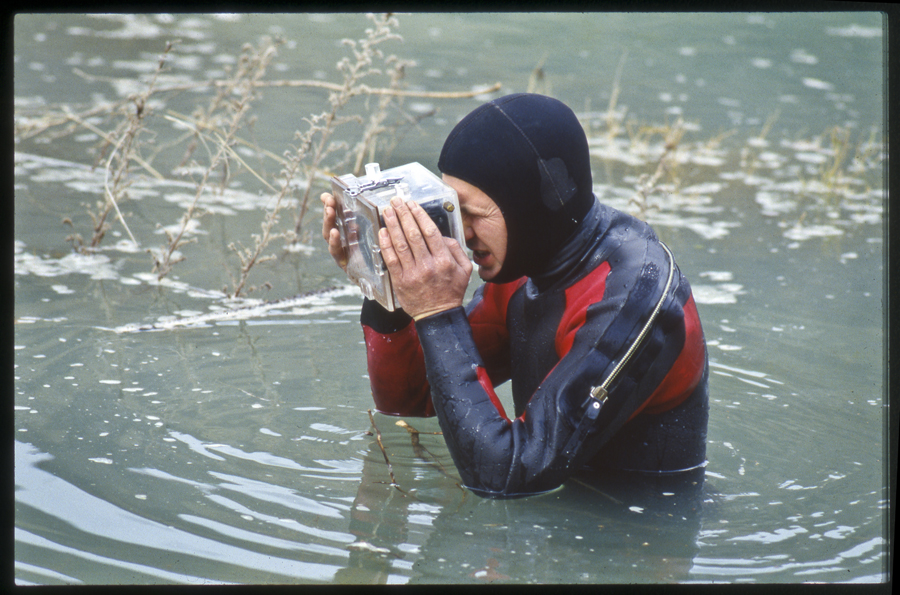

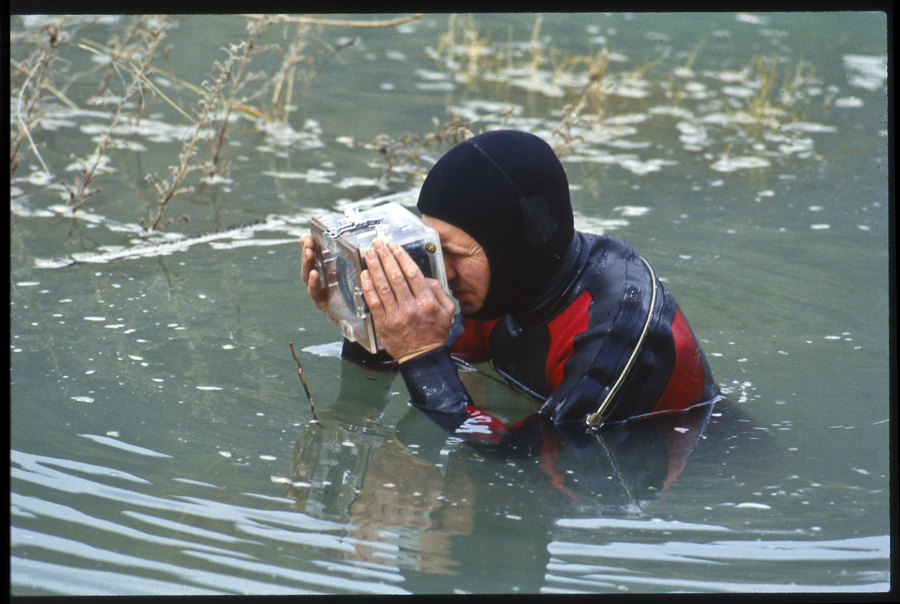

Over a period of perhaps 20 minutes, I slowly moved through the new

and surprisingly sticky mud of the shallows out into the deeper waters

of the filling reservoir. As I proceeded into these cold uncertain depths,

a series of photographs was taken until the camera lens disappeared

completely under the surface of this juvenile and virgin lake. At this

point, I was well free from the secure touch of the old land that had

only hours ago surrendered to become the new lake floor, and there I

drifted, betrayed by this false vestal of tranquil water, controlled

by powers beyond itself. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

After an uncertain time,

I turned and made a prosaic return to the shore where the white card

figure installation still waited, encircled by the surveying stakes.

Upon my return to dry earth I found a stick, floated off with the rising

water, and now lapping with a bulk

of debris and foam at the water's edge. Using a native rock as an unsophisticated

tool, I drove it into the silt at the very edge of the washing waters. |

| Having marked this present level, I was compelled to walk over to the

cut-out figure and with due ceremony, walked from the feet, up the body

of this curious configuration and then took one step out onto each arm

in turn. At this point my body sank down and collapsed prone, on top

of the now silt-soiled whiteness of the cut-out form. There I lay, prostrate,

an out-stretched black negative shape, identical, on the larger and

positive card cut-out below, the tonal contrast resonating on the terra

firma that would soon become engulfed in a watery tide created by technology. |

|

|

Inert, I lay there for possibly

20 minutes, absorbing, synchronizing, my breathing, and heart beating

as that of the earth. At one and as endangered as the condemned land

in the path of this eccentric oncoming force. |

To touch the Earth

a poem from - 1991

( From Drawing from Nature)

I lie on a high

hill, this mound of earth

I feel the sky vaulted above me

Below I sense growth and flux

The stillness vibrates a relaxed silence

I am nowhere and everywhere at once

Recharging, absorbing,

purifying

My heart is synchronised with a larger pulse

The vortex of an earth in space

An unfolding universe, a grain of sand

The intoxication of infinite spin

How am I above this organic growth

yet below its understanding?

I NEED TO RETURN AGAIN. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Later I rose as from a hibernation,

with an air of melancholy. I walked back down to the lapping water,

checking the new level of this ever-rising tide, then marked this with

another stick. It had risen nearly three inches from the previous

mark in the time I had been the earth. I had recorded the rise and the

time with two simple sticks. More water would soon cover much of the

earth I had always loved and possessed with my eyes and emotion, but

the turbulence of the wild blue river that had roared below here was

already gone!

At the time the television

crew seemed totally perplexed by the work, and they later informed me

that although the work was interesting and relevant they had decided

not to put it to air because it lacked something. But they mentioned

they would be quite keen to re-shoot and thought it would have more

appeal if I was prepared to do it again in the nude; to which I declined. |

Even with the initial filling

of the lake there continued a range of engineering problems that delayed

the continued filling of the dam. Drainage tunnelling and stabilizing

work emerge as an endless task and continued for months and at great

extra expense.

Later in the year, once

the new water level had settled and Electricorp was convinced there

was little threat of subsidence, it planned another raising of the lake

level.

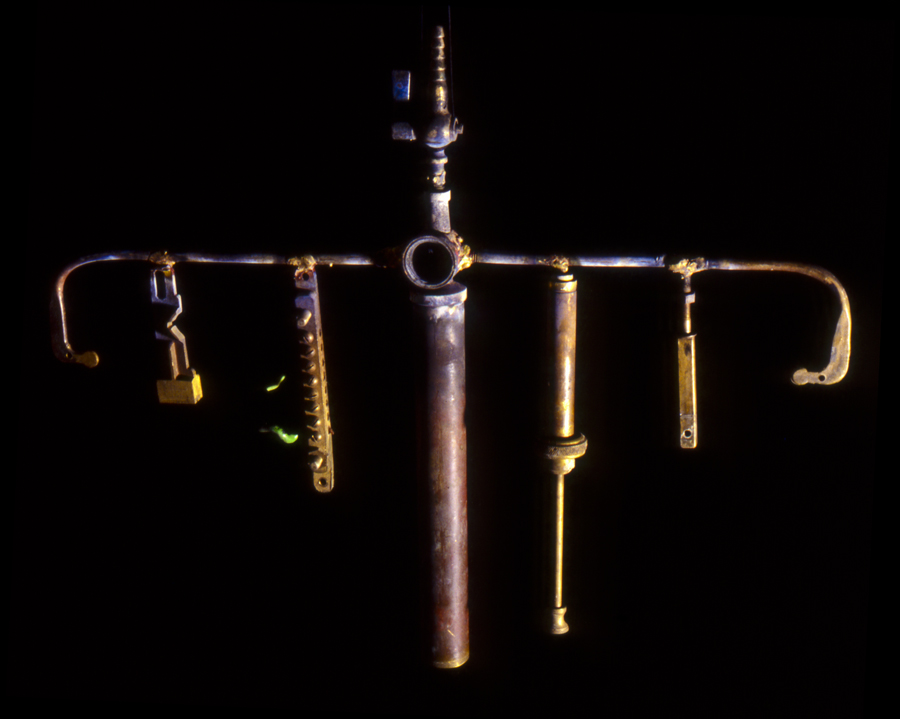

In the interim

I had given much thought about a second performance. Perhaps as delayed

hallucination from an electrical apprenticeship I endured when leaving

school, a response to the dam, or the sensitivity of the earth, I had

dreams, quixotic dreams, where I contemplated the earth and the river

as having its own gigantic "earth" electrical circuit and people as

an indirect extension of that circuit, or complex intricate components

of a whole. I dreamt of strange ceremonial artifacts, conducting rods,

dividers, induction coils, connectors etc artifacts from an invented

mythology religious items from a different power. Soon I engaged in

the making of conductive artifacts from the remains of discarded objects

of brass with past uses from past times. For months before the performance,

I scoured the local scrap merchant's brass bins, selecting potential

parts, laying them out to create new objects. I then fused these unrelated

items into structures that resembled strange religious artifacts.

|

Old taps, rods, worn door

knobs, parts of locks and pumps, rings, threaded bolts, long screws,

strange segments from forgotten artifacts with equally forgotten uses,

intricate moldings of their own aesthetic, these became the elements

that were arranged and then braised together to fuse them as new one

"new" singular object, eccentric objects that appeared to have some

ritualistic function. I formed the weekly habit of scouring the scrap

bins, arranging them into curious orders and braising them together;

continually, I forged item after item |

|

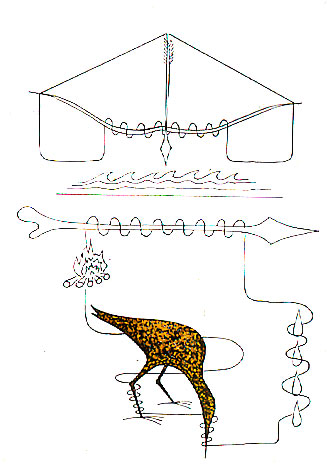

. I also work on a series of

"circuit drawings' where I investigated the idea of the circuits further,

where I investigated the "potential difference" between

objects, actions and consequence. Various objects that related

to the project were drawn as line drawings and linked by lines as in

an electrical circuit diagram. The lines would either be connected to

the object (bones, feathers, saws fire, rain clouds etc) or wrap around

it as an induction coil. People were represented and wired into the

circuit by a silver triangular plate representing one hand and a gold

one for the other hand. The drawings investigated the potential of direct

and indirect links between object/environment, cause/effect for the

proposed "earth circuit" second performance. |

Electricorp seemed to have

problem after problem and the date for the next level raising was postponed

and postponed, dates were confirmed and then moved. I had a trip to

Australia due and hoped that the next fill would not take place while

I was a way.

Eventually the next fill

date was announced to take place just two days before I was due to fly

to Australia, so with little notice and the series of ceremonial earth

stakes etc, dry suit and a few friends I scampered off up to the

dam site. This time I made no attempt to contact Electricorp for permission.

PERFORMANCE II Aug 1993 - Lloyd Godman

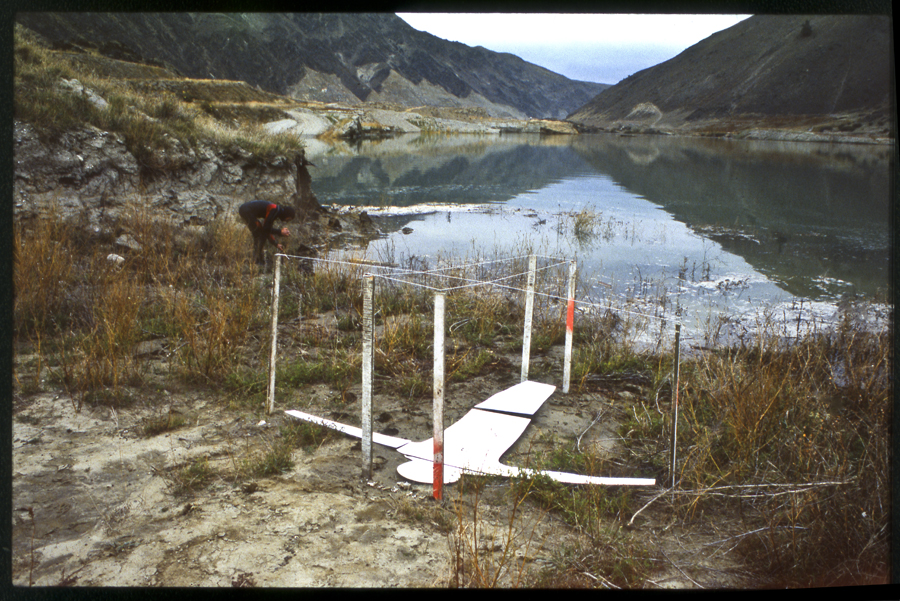

On arrival the first task

was to find a suitable site, a site with a flattish area sloping away

to the rising water a site that faced up the old dying river. As we drove

up and down the gorge searching for a suitable location, the topography

looked unfamiliar, no river flowed deep in the valley, it seemed strange,

and still does, to see the new lake flooded up the gorge where the river

had run with such power. Where the tributaries had joined the main river,

the junction points were different, the prominent rocky outcrops that projected from the water were all new.

| As with the first work,

the performance was done with a consciousness of myself as an integral

part of the environment, a fidelity and an attention to detail, in an

attempt to introduce a physical poetry to the event. After some searching,

I had found a suitable area for the performance. Although a little slanting

at the top, it ran down to the river from a great rock by the road side

and had a series of corrugations where it had recently been flattened

out by a bull dozer. It took some time to lay out all the "ceremonial

artifacts"; wire, clips, underwater camera housing etc. As in the first performance, I

dressed in the black insulation of a rubber dry suit and with slow deliberated

movements began to install the various components. First was the camera

itself which had to be positioned facing up the lake and to an exact

depth in the water so that the lens was giving an angle of view just

above the current water line. It also had to be held fast with a pile of large

rocks as any movement of the housing would ruin the framing for the

sequence of photographs. |

|

|

I ran a cable from the motor

drive of the camera though the housing up to the graveled beach.The conductive Artifact X male dividers were selected and I found a location to scribe a circle in the gravel, with there was a metalic sound as the instrument cut a line into the fine aluvial gravel and intermtantly connected with larger rocks. |

Next I selected the other dividers, conductive Artifact X Female dividers and again scribed a circle into the earth. |

|

|

Both pair of dividers were driven into the gravel at the waters edge and supported with large rocks so as they stood upright in contrast to the water. |

| At the centre of each circle an earth rod was drived upright into the gravel conductive Artifact XII Earth Rod |

|

|

A large log floating in the water was moved up the shore and positioned with its branches reaching out towards the advancing water. |

|

|

One

side of the circuit continued on from here and was connected to another

long length of wire which was wound as a series of metaphorical induction

coils around a range of organic objects found lying on the site: a branch,

some discarded feathers, a fern frond from a plant growing near-by,

a small thyme bush somehow ripped from the ground and now lying roots

exposed, bones, a large tree branch etc. Interspersed in the circuit

with the organic items were the "ceremonial artifacts" I had spent time

making in the weeks leading up to the performance - earth rods, dividers,

strange objects, which had earlier been used to scribe circles on the

beach. Appropriate "artifacts" were rammed into the soil, some in the

water, some on land, others were simply laid out on the gravel.

After the linking of these

objects, this side of the circuit ended clipped to a triangular brass

plate. My arms-width apart, I placed a similar copper plate and from

here the second part of the circuit ran directly back to the return

wire from the camera motor drive. The installation of this circuitry

was performed in slow methodical movements. Once the "Earth Circuit"

was in place I lay on the ground

arms out stretched to form a cruciform as in the first performance.

My hands were placed on the ground just below the metal plates, and

at interspersed intervals over several hours I would touch the two metal

plates which would fire the motor drive and record the increase of the

rise of the lake level. (When dressing, I had earlier placed a wire

in the black rubber dry suit from hand to hand across my shoulders,

and the symbolic connection was made through this wire).

However casual or premeditated

the act may be, the taking of photographs is a ritual. The scene is

selected, the framing adjusted, a light meter reading taken, the aperture

and shutter settings arranged, the lens focused and perhaps the procedure

checked before the shutter is tripped. The unacknowledged ritual takes

place thousands of times a day where the thought and emphasis is on

the image not the act. The ritual of making is generally forgotten,

the physical act happens on a subconscious level. Assimilating the photo-taking

act into the performance, where the process is linked directly to the

artifact, is quite distinct from taking photographs of someone during

a performance. As in the first performance, I incorporated this photographic

ritual as part of the work, and the final sequence of photographs are

a consequence of the work, not a document of the performance. While

the traditional ritual of taking photographs was combined with the ritual

associated with the constructed artifacts, the act was also removed

by placing the camera in the water and taking the images at random intervals

from a dislocated position.

Aug 1993

By the end of the second performance I had taken a second series of

photographs where the lake level had risen and obscured the previous

view up the lake. I deliberately left no distinct end to the performance

and our leaving, as I wanted there to remain a degree of indeterminacy,

the potential of a continuum.

end

Technical information for the Last rivers

Song - Project 1983-4

Cameras

Nikon F2 - used for land based shots

Nikon EM with power winder - used for shots from the boom suspended above the water

Linhof 4x5 Cardan Colour - used to copy prints onto 4 x5 film for the mural enlargements

Lenses:

20mm f3.8 Vivitar

50mm f1.8 Nikon series E

55mm f1.2 Nikkor SC

135mm f2.8 Nikkor Q

150mm f f.6 Symmar

Filters

K2 Yellow

YA2 Orange

25A Red

Neutral Density x2, x4, x8

Exposures : From 2min @f22 to 1/2000 @ f5.6

Films:

Pan F, FP4, HP5, Tech Pan

ASA Ratings:

3asa to 1800asa

Developers:

Michrophen, ID11, Perceptol, P.Q Universal, Tech Pan LC

Photographic paper Kodak Mural

Paper R3

Ilfobrom

Technique

All the photographs were first shot on on 35mm film using a variety of

approaches:

.

Time Exposure

Tech pan film and

Pan F were down rated and exposed through a series of neutral density

filters which allowed exposures of 2minutes at f22 in bright sunlight

with the camera on a tripod in the shallows of the river. The technique

was used for the images in Mural 4 and 5 and in panels 5,7, and threes

prints in panel 9.

Boom

The nikon EM was

suspended with the power winder on a retractable boom set on auto exposure

out and just above the river surface An accurate record of the exposures

was impossible to keep - but would probably range from 1/1000 sec to 1/30

sec. All these exposure were made using an auto exposure setting.

Gold

Toning

The

murals consisted of large composite photographic images up to 6-7metres

long and containing up to 7 prints 5'x 2 1/2'.

Selected

prints from this series were gold toned with native gold dredged from

the Clutha river and donated to the project by Bob Gray. The gold dust

was converted to gold chloride by Bob Cunningham from the Chemistry Dept

at the University of Otago, and combined with other chemicals in such

a manner as to produce either red and deep blue tones in the photographic

prints.

Soundscape

The enigmatic

electronic soundscape that accompanied the exhibition was specifically

composed by Trevor Coleman & Paul Hutchins for the installation in

1984.

Trevor

and Paul played live at the opening in the Dunedin Public Art Gallery.

|