River river on the wall - Kai Jensen - NZ Listener October 21 1984

These are not so much photographs as a deliberate attempt to drown anyone who walks into the east room of the Dunedin Public Art Gallery. They are whole rivers, suspended on the wall, with no guarantee that they will stay up there. These are waterscapes that will vanish, will themselves be drowned when the Clyde Dam fills.

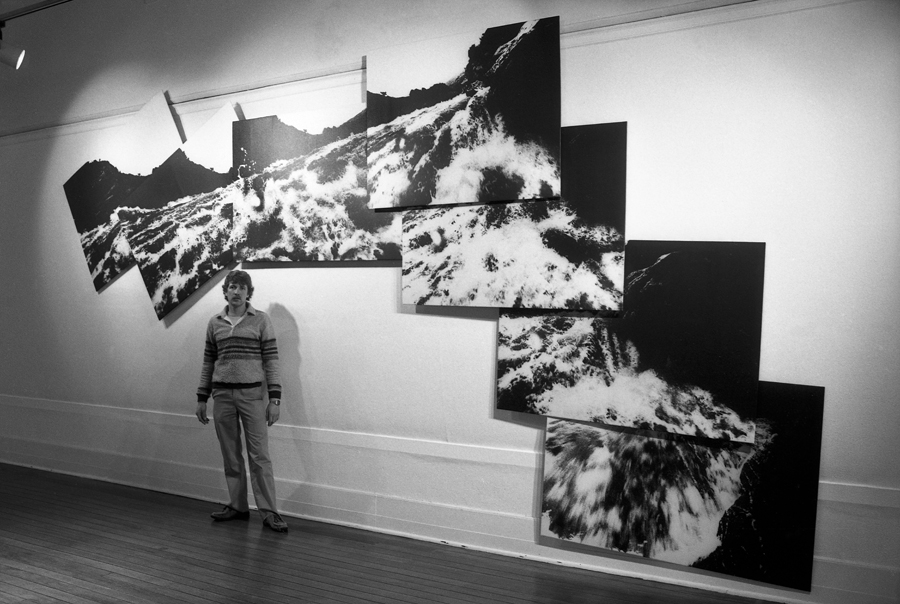

The enormous photo-murals of The Last Rivers Song, an exhibition by Lloyd Godman, are a determined assault on the human viewers by the inhuman energies of rock and water. They are, if you like, the rivers' revenge for the dam a denial that humanity exists.

On one all, the Kawarau River in flood is poised above your head in seven overlapping panels: a total mural height of three meters, width of seven. Godman used a five-metre camera boom and water proof housing to place our eyes in midstream, inches above the white water. The big Kawarau mural was taken during showers of snow, when the river was at its angriest - risen four metres. " Most people think a river just flows" Godman says, " but the Kawarau surges. I saw it flow down one side of a rock and then surge back up the other side, more like a tide than a river. To get this shot, however, I had to be down low. With such violence, with boulders being pushed around, I wondered what I was doing there."

The hard light of that snowy day and Godman's use of contrast create a savage effect: twin arms of rock and furious water reaching for you. Yet their foaming finger-tips dance with a strange, inhuman gaiety. This mixture of alien harshness and alien joy pervades the exhibition.

Meanwhile, your ears are full of the musical roar and piping of water as it grinds rock, the hiss of rock chips carried down the channel. Music composed and recorded for the exhibition by Trevor Coleman (synthesiser) and Paul Hutchins (flute) pushes you beneath the rivers' surface. This is not a purist's show of tidy, silent photographs, but "almost an installation" (Godman), a grand experiment, which comes close to outrage, risks melodrama.

You turn away, but there is no escape: high up the opposite wall the whole Clutha bears down on you: a royal procession of water. The Kawarau's wildness is absent, but the force of the water column descending the infinite gorge towards you is awesome. The end frames of this six-panel crescent are gold-toned with the river's own gold into a deep dark blue-black. The tenth of an ounce of pure gold used in the exhibition was donated by a dredge operator on the Kawarau.

The river gold over sepia tone produces a medley of rich reds and browns in a third mural, like the rust on an old freighters side. The mural is "smaller" : successive shots of one view, a rugged bluff from the water level. The red, used only on the middle panel, emphasizes the splash as the lens is wholly submerged. This effect, potentially a cliche', contributes here to a sense of the river's indifference to our observation: it is a slap in the face. It obscures the only hint of human presence in any of the five works on display, a tiny telephone pole atop the bluff. To Godman this pitiful artefact is a deliberate reminder of McCahon's symbol for "the crucifixion of the land".

This is the sole clue to the artist's outrage in the murals themselves. However, outrage courses through his typed commentary on the exhibition. And when he speaks of the dam, his disgust is emphatic. As a child, Godman spent many holidays in Cromwell with his family. The damming of the Clutha, which will submerge much of the Kawarau gorge as well, seems to him "like a bowel stoppage for the whole country". Other photographers have recorded the human history which will vanish in the lake, but Godman feels " they have missed the point."

Hence the determination to show the wild riverscapes which will be sacrificed for electric power we don't really need. This determination has sustained him through huge labour. He estimates that 600 hours have gone into the project, three expeditions to Central Otago and weeks in the Otago Polytechnic darkrooms, where he is a technician. He had to build special equipment to take the photographs, then build special darkroom equipment to develop the one by one-and-half meter sheets of "mural paper". His Central Otago trips yielded so much much material that a second exhibition, sequences of small river photographs, was held at the Marshall Seirfert Gallery in Dunedin. Godman refuses to estimate how much money it all cost him to the point where he handed the prints over to the Dunedin Public Art Gallery for mounting ( the gallery may chose one work from the exhibition in return for mounting expenses). He is amused to recall the photographer who said, early in the scheme, "But you can't do a project like this without a grant from the Arts Council" Godman did and as the murals went up for the exhibition opening he seemed numb in reaction to the end of all the work. Then another photographer asked him about the extremes of black and white in the hanging panels saying" I find it sinister."

The rivers pounce from the walls , a confluence of Kawarau and Clutha where we stand. But Godman is borne up - there is no need to drown if you love rivers so. " No not Sinister." I wanted to show a landscape before humans came to New Zealand, a pre-animal landscape... " He has succeeded so well in this, flooding The Last Rivers Song with both artistic and political force that his rivers may well flow onto other polished floors in other main galleries soon.

|

|

From - "from the river to the source" Lloyd Godman's ecological explorations

Lawrence Jones - Art Link Vol 25 no4

" In his landscape photography of the 1980s Lloyd created powerful black - and - white images of natural phenomena under threat in our consumption society. The Last River Song (1983-84) was a striking exhibition of photo-murals and panels, accompanied by original music by Trevor Coleman and Paul Hutchins, of the Kawarau and Clutha rivers in Central Otago as they flowed through the Kawarau and Clutha Gorges retrospectively. Many of the photographs were taken with a camera on a boom just above the freely and rapidly flowing rivers. As Otago Poet Brian Turner said in the introduction to the book that later grew from the exhibition, these are 'passionate and sensuous images' that show or imply that the forces at work are, on one hand, raw primeval, dangerous and on the other, seductive'. They also have an edge of sadness and anger, for, as the title implies, the high dam at Clyde on which construction was then beginning, would turn these gorges into an artificial lake and the mighty song of the rivers would be heard no more".

|

|

Lloyd Godman's Photography - Towards a Hyperbole of form

Alistair Galbraith - Art New Zeland no 47 Winter 1988

Lloyd Godman is tutor an technician in photography at the Otago Polytechnic's School of Art, beginning as a technician over a decade ago, submitting shots to amateur photographic magazines and surfing journals. However it was not until 1983 that his work began to develop its own style. It was about this time that he decide to focus on the New Zealand Landscape. Godman's subject matter is never trivial, his are permanent themes - the land, rivers, the form of the human body. He does not permit us a personal sentimental view of the subject, for in each he wants to call out a darkness, a primal strength of form.

Take the Last Rivers Song for example. Lloyd had decided to photograph the Clutha an Kawarau Rivers before they were dammed, but his intent was to document the actual moods of the water, its vitality and kinetic dynamism, not to eulogise over the orchards, fruit sheds or human dwellings that would be lost. The human element of life around the these rivers was visually insignificant to him, compared to the impressions of the rivers' force and power. He used a non-human point of view for this series - rather than working from the banks with long lenses, he built a 15ft retractable boom, with which he positioned a remote-controlled motor-driven camera very close to the surface of the water in mid-stream.

The results were divided into two groups - one of five large composite murals, and the other of thirteen smaller panels. The panels comprising, sixty-eight 175 x 100mm photographs were shown at the Marshall Seifert Gallery in Dunedin in September 1984, and the murals, made up from twenty-three huge prints opened at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery in the same month. The photographs in the panels were rather formally arranged in rows and columns, and over-all composition in each is a careful balance of black and white. Water surges, sprays, foams, whirls, ripples and rests, framed by very black rock which, when devoid of detail cameos the textures of its movements. In other instances a chiaroscuro lighting throws forward rock surface, its water-worn texture combining in rhythmic counterpoint with the current. The mural works are more expressively extreme, and have a greater over-all movement, each work capturing a different mood, from candy-floss fibres of foam in mural five, to the bone-crushing torrents in the second mural.

Standing beneath mural three ( which is about six feet high and 20 feet long) you even hear the roar of the water for a second. Your head tilts forward involuntarily a you experience a compulsive instinctual movement against the current. Your eye zooms up the narrow channel like a speedboat. The, insidiously, at the outer edge of your vision, you notice that the delirious flecks of spray are moving. This realization of so much time-structure on film.

|

|